by Rebecca Fraser-Thill

Have you ever noticed that the more free time you have in your day, the less you get done? If so, you're not just imagining it; many of us experience the same thing.

Have you ever noticed that the more free time you have in your day, the less you get done? If so, you're not just imagining it; many of us experience the same thing.

Does that mean we're all a bunch of lazy fools who cannot manage to get motivated without hard-and-fast deadlines nipping at our heels? Maybe. Maybe not.

Get Your Time Crunch On

Before we get into the laziness issue, let's establish why having less time tends to make us more productive: because it stresses us out – in a good way.

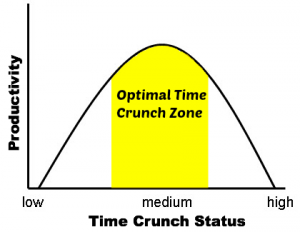

We need good stress, called eustress, to perform optimally, according to an old psychology maxim called the Yerkes-Dodson law. Not enough stress and we’re like sacks of potatoes on the couch. Too much and we’re a bundle of ulcer symptoms.

But I think there’s more to our “laziness epidemic” than a lack of stress. In fact, it’s just the opposite. It all comes down to an improper understanding our “Optimal Time Crunch Zone.” (It’s not as scary as it sounds – promise!)

But how do we know how much time crunch is “too much” and how much is “not enough”?

How to Find Your "Optimal Time Crunch Zone"

What feels like a ton of free time to me (a whole HOUR today?!?) may feel like nothing to you – or vice versa. So we have to do some trial-and-error to find what amount of free time works best for each of us.

We can do that totally randomly. Or, if you’re a dork like me, you can be a bit more strategic about the process, say, like this:

1. Identify your current Time Crunch Status.

- Signs of low Time Crunch Status = not bothering to do the things you want to be doing (e.g., the blogging, going to yoga and cleaning that you mention, Isabel), fatigue, lack of motivation

- Signs of high Time Crunch Status = irritability, forgetfulness, exhaustion, missing deadlines, physical ailments like headaches and digestive issues (all sorts of fun!)

- Signs of being in the "Optimal Time Crunch Zone" = You aren’t worrying about this issue at all! Things are just flowing.

2. Jot down your Time Crunch Status AND how many hours a day, on average, you currently have “free” (i.e., the hours you get to fully determine what you’re doing).

- Put these notes somewhere you can refer back to them months – or even years – later.

3. If you’re not currently in your "Optimal Time Crunch Zone," tinker with your Time Crunch Status.

- If you are experiencing low Time Crunch Status: try adding a bit more requirements to your day, such as by taking on a volunteer position.

- Notice I said “adding a BIT more” – I’ve seen many students take this too far too fast, passing right by the Optimal Time Crunch Zone into danger territory. I must admit I did this at the start of my first few semesters of college: workload felt so light during the first two or three weeks that I signed up for a ton of activities so that I didn’t have so much free time. I’m sure you can imagine what happened to me by midterms. Ugly.

- If you are experiencing high Time Crunch Status: Uh, yea. This one is difficult and I’m no master here. In theory, we should list everything we have on our plate, prioritize that list based on what each brings into our lives (both extrinsically and intrinsically), and then pare off the bottom items one by one until we hit our "Optimal Time Crunch Zone." In practice…uh, yea.

4. Continue to tweak and keep track until you see your personal pattern emerging. Then you’ll know what’s too little free time for you – and how many hours is too much!

- In my experience, our “need for time crunch” remains remarkably stable over time. When I think to my friends from high school, I can think of some people who LOVE to be crunched to an extent I couldn’t stand, and others who wouldn’t want to endure my pace. Although just about everything else about us has changed in 20 years (good bye frizzy hair!), our individual "Optimal Time Crunch Zone"s haven’t moved much at all.

The Scoop on “Laziness”

Now that we're clear on why we're more productive when we're busy, and how to optimize our productivity, let's finally tackle the laziness issue.

Although Peter from Office Space claims he’d “do nothing” if he never had to work again, I don’t believe him. Nobody is that inherently “lazy.” All humans have what psychologists call stimulus motives, which are motivations make us feel horrendous if we’re not stimulated “enough.”

I believe “laziness” arises from a simple lack of understanding of our "Optimal Time Crunch Zone."

I'm convinced this lack of understanding is epidemic. We’re a culture so obsessed with being busy, we experience tons of burnout that LOOKS like laziness.

In other words, we operate so far above our "Optimal Time Crunch Zone" for so long that when we finally get a moment to chill out, our bodies scream for us to STOP. Completely! Then we berate ourselves for not getting anything done.

Pretty ridiculous. (But I am SO a victim of this - at this very moment in time!)

Once we get clear on our "Optimal Time Crunch Zone," however, we know precisely how much we need on our plates to feel productive and energized. THEN we can work on breaking the “overly busy/overly tired” cycle by respecting our needs.

That said, the “respect” part is something I’m still very much working on! My strategy? Intentionally spending time around people who operate in their "Optimal Time Crunch Zone" on a regular basis and hoping they rub off on me. (Still hoping...)

That’s the best we can do, though: become aware of our patterns, look for healthy models to help us break those patterns, and forgive ourselves when we (inevitably) slip up.

One day at a time. One hour as it comes. One great Time Crunch moment behind us yet again.

We’d love to hear from you in the comments below:

How do you find the balance between being stressed and being bored?

About Rebecca

About Rebecca

Rebecca Fraser-Thill is the founder of Working Self, a site that helps young adults create meaningful work - that actually pays the bills! She teaches psychology and is the Director of Program Design for Purposeful Work at Bates College. Her work has been featured throughout the media, including on The Huffington Post, The Chelsea Krost Show, and Stacking Benjamins. Follow her @WorkingSelf.